Do you even know what you're Tolkien about?

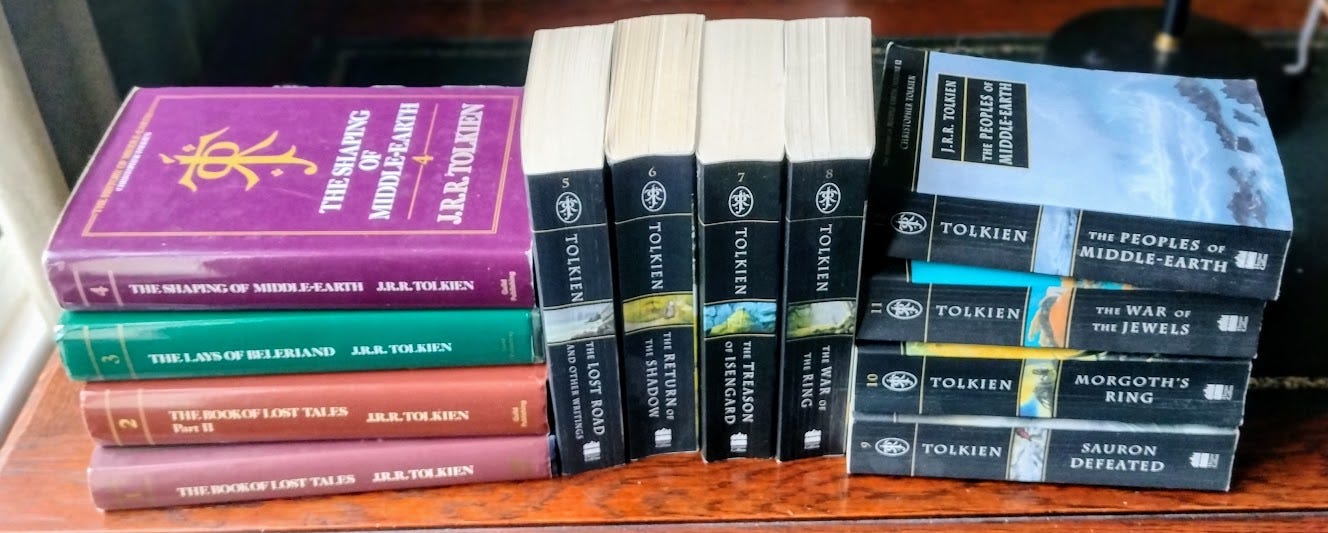

After putting it off for decades, I made myself a pledge last year to read The History of Middle-earth: 12 volumes, 12 months — a book a month. Was it worth it?

In order to write this post, I find myself looking through each of the 12 volumes to refresh my memory, and locate the bits I marked with pencil. The standard format for a chapter in the histories is to present one of Tolkien’s tales, sometimes with a brief introduction, followed by endnotes, then a commentary by the editor (his son Christopher). There are occasional chronologies, maps and family trees. There’s the odd chapter on language or etymology, which were sometimes so technical that I skimmed over them. Some of Tolkien’s writing takes the form of poetry, and there are even one or two poems in Old English, which I didn't even attempt (but it’s nice to have them included for those that can read it).

The histories present a deep dive into each of the stories that (mostly) appear in The Silmarillion. In retrospect, I think I would have gotten more out of the histories had I refreshed my knowledge of The Silmarillion first. I’m now filling in some gaps by working my way through the Nerd of the Rings YouTube channel (which I recommend).

Tolkien loved language in a way that I struggle to appreciate, and something one hits pretty quickly are name variations. We get a taste of this in The Lord of the Rings (LotR): Gandalf has the alternate name Mithrandir; Aragorn is introduced as Strider (each of them has other names besides). This is turned up to 11 in the histories. For example, at the end of the first chapter of Book of Lost Tales 1 (Cottage of Lost Play), we learn that ‘the Gnomish (yep gnomes, get used to it) name of Tol Eressëa was changed many times: Gar Elgos > Dor Edloth > Dor Usgwen > Dor Uswen > Dor Faidwen.’ I quickly decided I was going to gloss over notes that detailed many of the name variants — there’s no way I’m going to remember so much detail, my brain would melt.

The Silmarillion and the majority of the material in the histories, has the feel of legend, which reads quite differently compared to the narrative that we get in a novel. A novel, such as LotR, gives us drama, dialogue, character and detail. It focuses in on key characters — we feel like we’re there with Bilbo and Gandalf in Bag End. I don’t get that immersion when reading The Silmarillion, I’m not sure how to express the difference. I had a similar experience reading Beowulf. I feel like I’m one step removed from the story, like it’s been recounted to me (much of the speech is reported rather than direct). Not that this is a criticism, indeed, Tolkien was of course a scholar with a focus on texts such as Beowulf, and this was what he was aiming for.

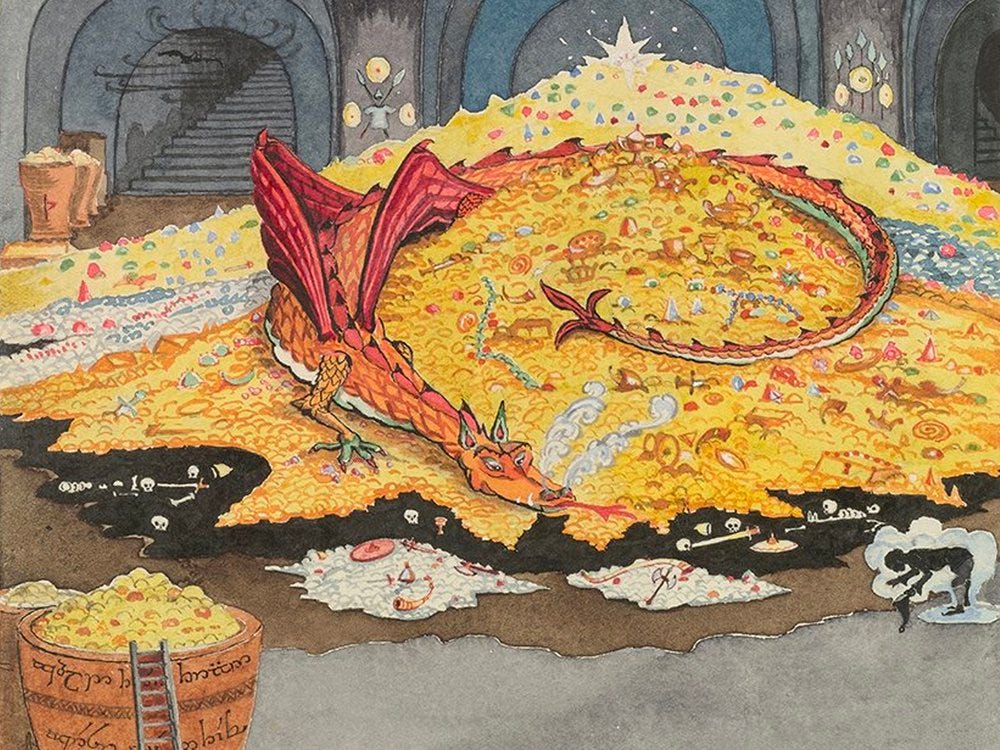

One of the things that really strikes me about Tolkien is the variety of ways in which he worked. He created his own languages, which to him suggested peoples and cultures, leading him to create myths and legends. This fed into his fiction, from which grew The Hobbit, LotR and The Silmarillion. But it doesn’t stop there. He also wrote poetry (and songs), and we see these throughout his books. When I first read The Hobbit, both the Dwarven runes and the maps made an impression on me, both of which he drew. Indeed, he clearly loved to draw, and created illustrations of scenes from his books, some of which were used as book covers. He really was an all-rounder.

I wonder what it is like to work in so many different ways, and if it is something that we can learn from. It’s easy to see some parallels in the roleplaying games hobby. Creating fiction is a core element of RPGs: as GMs we write scenarios; as players we write character backgrounds. This is often supplemented with a pick and mix of creating handouts and props, drawing maps, painting minis, and drawing character portraits. It also extends now to creating podcasts and videos. I love how this provides a variety of ways in which people can engage with the hobby.

I feel like each of these creative endeavours strengthens the whole, and that sometimes they feed into each other. I know from my own experience that when I draw a house plan for a scenario, it will sometimes spark ideas that feed back into the writing. Returning to Tolkien, on page 65 of The War of the Ring, there’s the following:

I knew nothing of the Palantiri, though the moment the Orthanc-stone was cast from the window, I recognised it, and knew the meaning of the ‘rhyme of lore’ that had been running through my mind: seven stars and seven stones and one white tree.

Tolkien composed a rhyme of lore without knowing what it meant — I guess it just sounded cool. The poetry fed the fiction, or at least connections were made between the two, and both the fiction and the poetry took on greater meaning because of it. That feels like a little bit of magic to me.

He died in1973, a year before Gygax published D&D, but I wonder what sort of DM Tolkien might have been, had be been born in say 1962 rather than 1892. But then again, would D&D (and thus RPGs) have happened without Tolkien’s creations?

Tolkien left us his life’s work, and clearly there’s a lot to get into. I’m pleased that I have read the histories, though much like a marathon (or so I imagine), reading them was hard going in parts, but I’m glad I made it to the end. The books have deepened my understanding of Middle-earth, but they’ve also shown me how much more there is to get my head round. I was about to type that I’m looking across the room at a pile of books on the floor under the TV, but as I looked up I realised my wife has tidied them away. Anyhow, hopefully I still have a pile of 12 books somewhere in the house, and I think I’ll be dipping into them for years to come.